In a previous article, we discussed therapies that might affect the cancer-immunity cycle. Today’s article continues that discussion by reviewing the guidelines for the evaluation of immune therapy activity in solid tumors.

These guidelines were published in 2009 in Clinical Cancer Research in Guidelines for the Evaluation of the Immune Therapy Activity in Solid Tumors: Immune-Related Response Criteria by Dr. Jedd Wolchok. It’s the paper that everyone quotes, but not everyone has read.

This article was written for Chief Medical Officers, researchers and all of those focusing on continuing development in this field. It is based on Dr. John Grous’ presentation from our webinar: How Immune-Related Response Criteria Is Changing Immunotherapy Treatments.

Medelis has been managing immunotherapy studies in oncology since 2008. We work directly with sponsors on the development of clinical strategy (protocol, endpoints, regulatory) and with study execution in this growing field.

The Wolchok paper was generated through workshops in 2004 and 2005 of oncologists performing immunotherapy. In the workshops, the oncologists anecdotally noticed that immunotherapy may be different from classic cytotoxic therapy in that you may see delayed responses or responses in the presence of new lesions.

They wanted to scribe some of these observations (as there are responses to immune therapies that occur after conventional progressive disease by either WHO or RECIST) and communicate that discontinuation of some of these immune therapies too early may not be appropriate in some cases. The oncologists wanted to create an allowance for “clinically insignificant” progressive disease, either the first time or during the development of small new lesions, which should be considered in the overall tumor burden.

Durable stable disease may represent antitumor activity (which is true for all cancer therapies), and they suggested to develop a new clinical paradigm and to refine response criteria to address these concerns. The team, led by Dr. Wolchok, other academics and other industry insiders decided to review three large phase II studies mainly in 487 advanced melanoma patients who were treated with Ipilimumab, to study and refine the response criteria.

Before we discuss their findings, here is a refresher about Ipilimumab.

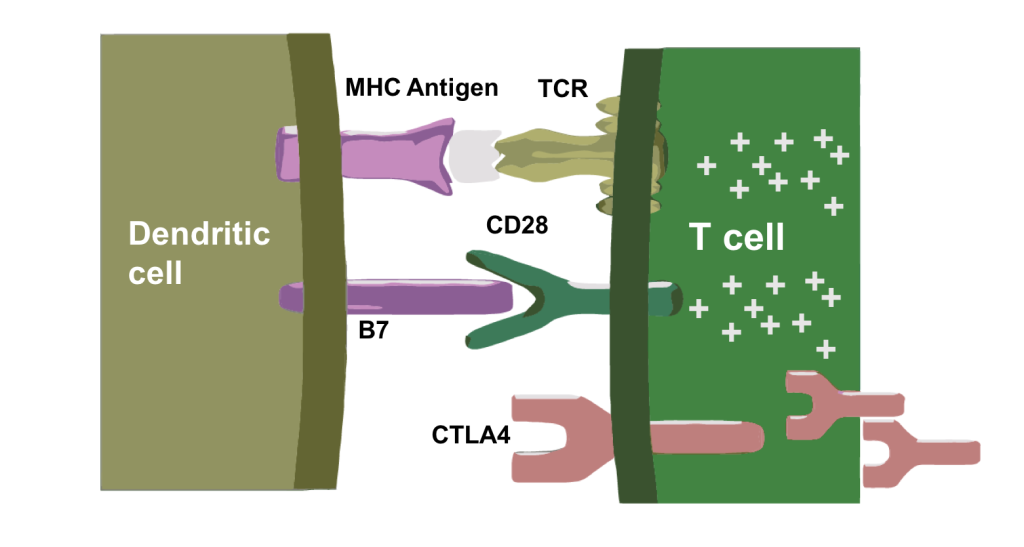

Ipilimumab blocks CTLA-4. Interesting enough, CTL4 can be not only be induced by T-cell priming, but also by the tumor. Blocking it basically inhibits the inhibition and can activate antitumor T-cell activity.

The antigen is presented by the dendritic cells to the T-cell receptors and the host immunitory B7 molecule binds to CD28 which up-regulates the CTLA-4 receptor.

Antigen Presentation and T-Cell Priming

Antigen Presentation and T-Cell PrimingThis is the mechanism where the priming and co-stimulation increases NF-β and nuclear transcription, and also induces survival mechanisms by inhibiting some of the apoptosis proteins. The CTLA-4 is contained in vesicles made by the Golgi apparatus which will be expressed on the cell membrane.

This shows that B7 binds both an activating receptor (CD28) and an inhibitory receptor (CTLA-4). CTLA-4 has more affinity for B7 than CD28. This is a normal immune checkpoint in our immune system that controls rampant immune responses to infections and is also involved in the prevention of autoimmunity.

Here are some of the intercellular pathways that are affected by both B7 binding and CTLA-4. You can see the programmed death 1 (PD1) receptor that’s binding to PD-L2. That’s one of the ligands that binds to PD-L1.

Here is a summary of essentially that whole mechanism of antigen presentation, co-stimulation with B7, which gives you an activated T-cell in the right environment and then CTLA-1 being expressed and up-regulated which in turn inhibits T-cell activation and blocks the receptor.

When the investors reviewed the 487 Ipilimumab monotherapy patients, they found four distinct response patterns:

All of the responses were associated with favorable survival. Further prospective evaluations should be validated in a controlled trial.

The diagram of those four responses is below and shows the initial response, stable diseases, progressive disease and response in presence of new lesions.

The authors used WHO criteria (which was superseded by RECIST in 2000), in which you basically multiply two bi-perpendicular diameters of a tumor areas and then you sum the products, so it’s more cumbersome. There are different thresholds for response and progressive disease. For response, you need to see a 50% decrease in the sum of those bi-perpendicular products while for progression it’s a 25% increase; whereas in RECIST we’re just taking one longest diameter measurement of the tumor size and then summing those. A 30% decrease in the sum of those is a partial response and a 20% increase in the sum of those longest diameters represents progressive disease.

Out of 167 patients, there were 22 that had progressive disease (initially by WHO) that later had a delayed response; five of them reached partial response and the other 17 had stable disease. The irRC does pick up those variations in response.

There were 63 patients and overall survival was 31 months. The top curve in the below diagram represents the patients who responded or had initial stable disease. The middle curve represents the 22 patients who initially progressed and then either had a response or stable disease (and the overall survival hasn’t been reached in that group). The last curve represents the 137 patients that were either lost to follow-up or progressed initially with an overall survival of 5 months.

This shows that the irRC does help in patient management and can be reflected in survival.

Here is a diagram of what we think is happening in the initial pseudo-progression, where the tumor is infiltrated by various immune cells. There’s inflammation and there may be edema, so you get an increase in the tumor size before you see a killing or decrease of the tumor.

After analyzing the patterns here, the authors wanted to tweak the response criteria. They found:

The first PD in the irRC is called unconfirmed progressive disease, and then the second scheme which confirms it is called confirmed irPD.

This is the table taken right from the paper. New lesions are incorporated into the tumor burden. With WHO you multiply by the perpendicular diameters and add the sum of those diameters to the total tumor burden. That can be added to partial response, stable disease and PD with the same criteria.

The difference between irRC and WHO is that WHO allows lesions as small as 5mm whereas with the irRC, you’d only add those lesions once they became target lesions or measurable, which is 1cm.

Again, for progressive disease you need to confirm it with two time points no less than four weeks apart.

There was an editorial in the same journal by a renowned immunotherapist which collaborated the irRC approach. There are limitations to it because it’s only one immunotherapy and only one tumor type – advanced melanoma.

Interestingly enough, most of the immunotherapy protocols I’ve worked with have incorporated this, but it’d still be nice to see it confirmed in a large clinical trial.

If you’d like to talk with us about the design or management of your upcoming immunotherapy study, connect with us.