Vaccines are at the top of everyone’s mind in February 2021 with the rollout of multiple COVID-19 vaccines. The two-dose Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna mRNA vaccines are the first of their type to be approved for use in any disease.

While the concept of the mRNA vaccine is simple, it required decades of work for mRNA vaccines to be developed. Scientists had to

In addition to being easy to produce, mRNA vaccines can actually generate a stronger type of immunity by stimulating the immune system to make antibodies and immune system killer cells.

Could this approach work for cancer?

Researchers are optimistic. Cancer vaccines are part of immunotherapy treatments that have been in the clinic for over a decade. Doctors give treatment vaccines to people who already have cancer, and these cancer vaccines can keep the cancer from coming back, destroy any cancer cells still in the body after treatments are completed, and stop a tumor from growing or spreading.

Often, cancer cells have certain molecules called cancer-specific antigens on their surface that healthy cells do not have. When a vaccine gives these molecules to a person, the molecules act as antigens. They tell the immune system to find and destroy cancer cells that have these molecules on their surface.

Cancer vaccines can be personalized – produced from samples of a person’s tumor – or targeting certain cancer antigens that are not specific to an individual person.

Most cancer vaccines are only offered through clinical trials. Provenge (Sipuleucel-T) was the first cancer vaccine approved by the FDA (in 2010), targeting metastatic prostate cancer. Sipuleucel-T is tailored to each person through a series of steps:

Precision Lifesciences Group (PLSG) is developing patient-specific immunotherapy products. The ICT-107 is Phase 3 ready for newly diagnosed glioblastoma multiform (GBM). The ICT-121 is Phase 2 ready for recurrent Glioblastoma and the ICT-140 is Phase 1 ready for Ovarian Cancer.

Clinical trials are key to learning more about both cancer prevention vaccines and cancer treatment vaccines. Researchers are testing vaccines for many types of cancer, including:

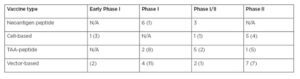

A recent search on clinicaltrials.gov for cancer vaccine returned 58 early Phase I and combined Phase I/II, and 25 Phase II cancer vaccine trials that are actively recruiting (from EMJ):

Summary of open vaccine trials with and without checkpoint inhibitors.

Number in parentheses reflects the number of trials without immune checkpoint inhibitors combination.

There are numerous challenges of using treatment vaccines in the clinic:

Cancer vaccine development looks extremely promising, and we expect that many will contribute to this promising area of research in the 2020s. Medelis has been at the forefront of immunotherapy research since 2008, focused on partnering with companies developing these therapies in the clinic.

If you’re planning your first cancer vaccine study, we recommend planning to overcome these six common causes of delays in immuno-oncology studies.

Additionally, here are tips for preparing for your first phase I oncology study.

If you’d like to have us review your study plan, feel free to contact us.